Transcript included below…

Ok, so I’m about to embark on a subject that may be a little controversial, because I’ll be making some claims that are not necessarily flattering about other musicians.

It’s not my intent to be hurtful in my remarks, but rather objective, with a view to enhancing the learning experience from both sides.

If you know me, you know that I consider criticism, especially constructive criticism, to be a gateway to musical maturity…but we have to walk through that criticism and consider it carefully so that we can get to the rich music that’s waiting on the other side of that gateway.

When it comes to learning the guitar (or any other skill), not every guitar teacher out there currently has the heart of a teacher. And not every guitar student currently has the heart of a learner.

As we continue forward, please consider my use of the word “currently” as an acknowledgement that we are all works in progress, and although some of us may not change our trajectories in the direction of improving our approach, many of us may do so.

I’ve been on the receiving end of the teaching approaches of some phenomenal guitarists, for which I’ve paid top dollar, and sometimes traveled a great distance.

As grateful as I have been to learn from these teachers, I won’t specify the names of these guitarists, because it doesn’t really matter who they are – I’m more focused on what we can learn from their approaches.

Many of these guitarists are astounding musicians, and often very gifted performers who can connect with an audience in an incredible way.

But for some of them, their ability to teach, to break down concepts into accessible, progressive steps, can be quite limited.

I’ve also taught students who were either impatient, wanted a shortcut or an easy fix, or they didn’t see the validity in taking a “step by step” approach.

Exempli gratia – I had a prospective student who had never played the guitar tell me that the first thing he wanted to learn was “Purple Haze” by Jimi Hendrix – exactly the way Jimi played it.

However, after I took a few minutes to encourage this prospective student to consider developing some basic guitar chops first, to build up to learning a challenging song like this, the conversation ended, and I never saw him again.

Let’s face it: some people can’t currently effectively teach what they do. And other people aren’t currently teachable. These are facts.

Now, once again, I’ve used the word “currently” to qualify these descriptions of teachers and students. And that’s because I have great hope that people can change for the better…if they desire to do so.

Someone who doesn’t currently have the heart of a teacher could invite the Lord to change their heart. The same goes for a student who is not currently teachable. They could pray for the Lord to renew their mind so that they can have a healthy hunger for musical knowledge.

Now, in my opinion, it’s ok if someone does not have the heart of a teacher, and it’s also ok if someone is not teachable.

If just one of these scenarios is in play, great things can still happen. If both are in play, progress is much more difficult.

Track with me here as I try to quantify something that’s hard to quantify.

I’m including some diagrams I’ve created, because I’m very visual as a teacher and as a learner.

If the knowledge distance between a teacher and a student is defined as a connection of 100%, for the teaching to have application, there needs to be effort on both sides to bridge the knowledge gap.

If neither the teacher nor the student has the desire to bridge that gap, then it can be very difficult to experience progress and growth, and at the very least, it can be frustrating and exhausting.

In an ideal scenario, both the teacher and the student have the heart to connect and to allow the learning process to happen, unhindered. We could say that each can reach to the other with 50% of the effort, to create the cumulative 100% of the effort that’s needed.

This, to me, is an excellent formula for an effective teaching and learning environment.

And frankly, if we have a teacher with a huge heart for teaching and a student who is a passionate, teachable learner, we might have 75% of both sides reaching toward each other, exceeding the 100% and creating an exceptional environment.

However, not all scenarios are exceptional, or even ideal, so it’s important to recognize what causes the obstacles and hindrances on both sides, and what sort of solutions can be put into place to break past those obstacles.

The Teacher

Let’s talk about the teacher’s side of the learning experience first. If the teacher has a solid musical background, he or she has probably developed their skills to quite a formidable level. And this can be a good thing.

But let’s not assume that their skill set equals teaching ability.

There exists a curse among some highly talented and experienced musicians who endeavor to teach, and it’s aptly called “The Curse of Knowledge,” which is part of the title of this episode.

How can knowledge be a curse?

Well, under these circumstances, if a highly experienced teacher is addressing a less experienced student, that teacher may really struggle to remember what it was like to go back to the early stages of his or her musical development…and therefore, he or she can’t effectively break down the step-by-step process to help that student make measurable progress.

The teacher is trapped in their current state of musicianship, and cannot systematically retrace their steps. This is the Curse of Knowledge.

Let me share a few examples of teachers whom I believe to have had the Curse of Knowledge.

I attended a masterclass with one of the most gifted guitarists I’ve ever known, and this individual, though a tremendous musician with incredible showmanship, did not seem able (or willing) to break down the guitar concepts that were offered.

When I asked a very specific question of this teacher related to a practice regimen and what sort of step-by-step process could help us improve as we play, this guitarist simply said, “Well, I just do this,” and a blisteringly fast guitar lick emerged under their fingers, and we were on to the next question.

Everyone in the room was wide-eyed, both in awe and in confusion. No one seemed to have any grasp of what was being communicated…and perhaps inspiration was all that was really needed for many of them at that stage.

But for those who wanted to learn the specifics of what was being demonstrated, they were at a loss, because there was no structured, logical approach to breaking any of the guitar concepts down or connecting ideas together, in spite of all the questions from myself and others.

Music doesn’t always need to be logical, of course, but we can save ourselves a lot of time and frustration if we incorporate some sort of framework at certain stages.

So, whether he or she consciously knows it or not, a guitar teacher (or any kind of teacher) who can command an instrument and demonstrate a skill, but who cannot take the skill apart so as to teach it…is under the Curse of Knowledge.

I attended another guitar education experience as a student, where criticism from a virtuosic teacher was offered to the students, but accompanied by very few tangible solutions with concrete steps for improvement.

“Don’t do that” was basically all that was said. Constructive criticism is definitely an important aspect of teaching, but I always believe it should be provided hand-in-hand with specific suggestions for an alternative approach, with a view to progress.

Here in this environment, the Curse of Knowledge was once again looming, because it was clear that the highly gifted guitarist was not in a posture to be able to graciously provide the teaching that the students desperately needed to improve.

As a linear teacher and learner, I always appreciate the opportunity to guide a student, or sometimes a group, along the continuum from knowing less, to knowing more.

But when I attended a recent workshop with a virtuosic guitarist who was more of a performer than a teacher, it became clear that certain topics needed to be at least addressed, if not unpacked, in preparation for the topics being discussed. There were prerequisites that needed to be considered.

It’s hard in a workshop environment, because people may be coming from multiple skill levels and backgrounds in music, but this teacher, kind and gracious though he was, assumed a level of musical understanding that wasn’t there for a large portion of the class.

So, while a few students tracked with him through a more advanced discussion, many were confused and didn’t have any sort of foothold as the teacher moved swiftly through some pretty difficult concepts.

Again, some of the students were inspired, but many really only needed a quick review of the “prerequisites” and they would have found their way, at least through some of what was being discussed.

Instead, the Curse of Knowledge kept the teacher moving quickly, as many of the students were left scratching their heads.

The Student

Let’s now turn our attention to the student. He or she may be a beginner, an intermediate, or even a “lateral learner,” who may be new to the guitar, but not new to music.

The level of skill or knowledge for this student is not of consequence. What’s important is their posture.

Do they want to learn? Do they see others as teachers, even their peers? Can they learn from anyone, or do they assume that they have the answers?

I’m sure you’ve heard the tongue-in-cheek expression, “Hire a teenager while they still know everything.”

Well, it’s not just teenagers who are prone to this skewed mentality. The reality is that none of us know everything, even if we are under the impression that we know a lot.

Even if you were to present me with the most skilled guitarist on the planet, there would still be things they would not know.

In my opinion, teachability is either present or it’s not.

And if a student is not teachable, they are under the Curse of Knowledge; there’s an artificial ceiling they have built above them that they will not be able to break through.

I’ve met many guitar players who fit this description.

The Teaching and Learning Environment

Now, we have to consider the environment in which teaching is offered.

I’ve taught (and learned) in an environment where there has been one teacher and as many as 100 guitar students in a single room.

This is more of a one-hour masterclass environment, where the best approach to relaying information is to “aim for the middle” and hope that everyone will walk out with at least one new idea to take action with.

By contrast, a one-on-one guitar lesson presents a significantly different dynamic, because obviously there are fewer variables, but also, the pace can be much slower.

Even in spite of these varying scenarios, the Curse of Knowledge can still hover over the teacher or the student. It’s unfortunate, because important, useful, and actionable information can still get lost in the mix.

What to do?

The Student Bridges the Gap

I do have a strategy for the student when the teacher does not seem to be able to break the Curse. And here it is: it is…to self-teach.

That’s a simple way of saying that with the right mindset and an eye and ear for detail, a guitar student can closely observe what is being demonstrated by his or her teacher, and break it down into smaller steps…even if the teacher does not.

I’ve done this more times than I can count. Usually, it involves capturing what is being demonstrated on video, so I can go back for multiple viewings, sometimes slowing down the recording to observe the subtleties.

But even without a video recording device in my hands, or without access to a video version of the concept on the web, I have still found myself leaning forward, focusing, and quietly describing to myself what I observe, sometimes quickly writing things down.

Let’s go back to our quantifying approach for a moment.

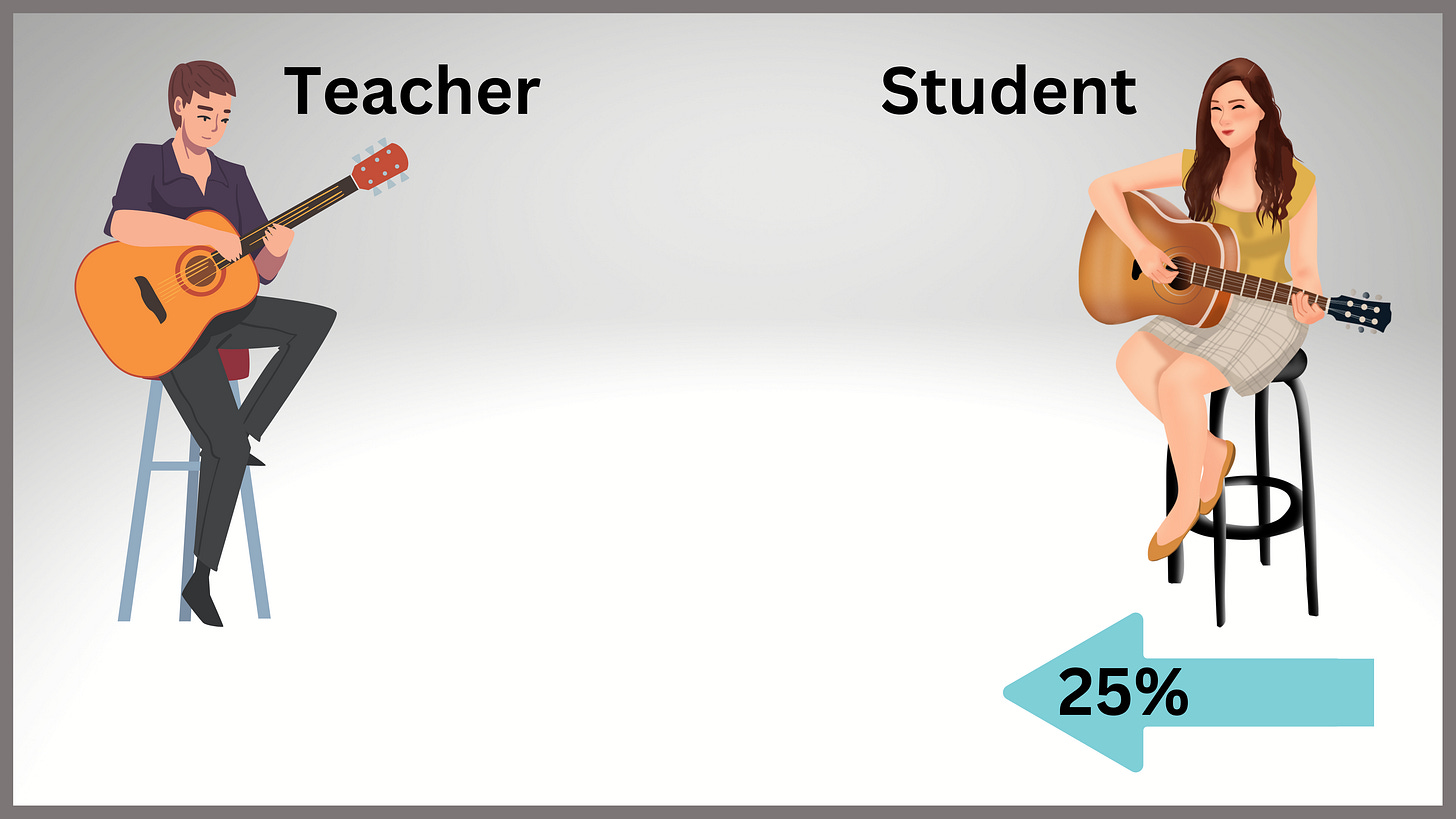

If a teacher is not in a posture of reaching 50% or 75% of the way towards a student, but rather is more like 25% of the way, it’s up to the student to reach 75% of the way towards the teacher, in the hopes of gleaning some of what the teacher wants to convey.

For the student in this scenario, having a level of musical literacy can be tremendously helpful.

I’ve been able to develop my ear training to a level where I can hear chords or even melodies, even without a video reference, and to be able to transcribe what I hear so that I can replicate it later on my guitar.

So, even if I’m not at a point of being able to physically duplicate what’s being demonstrated by a guitar teacher in the moment, I have developed two vital skills.

The first is ear training, which allows me to hear and recognize what’s happening.

The second skill is called melodic dictation, where I’m able to transcribe what’s happening, into the language of music, whether chord names, chord shapes or even more specifically, notation and tablature.

Once I have the music captured on paper, or in the notation and tablature software on my computer, I can systematically go over it later and gradually put it together.

This process has literally made the difference between being able to learn and play something or not.

Ear training and melodic dictation are life-long skills to be cultivated and developed over the course of our entire guitar journey.

If we carry these strategies into the digital sphere, software has been developed to transcribe what is being spoken or sung, and what is being played as well.

A word of caution, here, though…the guitar has multiple instances of duplicated exact pitches, so it’s still up to the guitarist to figure out which scale, chord, or capo position is being used.

And sometimes, we can err on the side of using technology as a crutch, rather than to use the challenge as an opportunity to strengthen our abilities.

As you can see, there are many practical approaches the student can take to lean into what is being taught, even if it isn’t being broken down in a teaching fashion.

Even if the teacher is only coming 25% of the way, the student can reach 75% of the way to make the connection complete.

The Teacher Bridges the Gap

Let’s look at this from the teacher’s perspective when a student is not demonstrating the heart of a learner.

Perhaps the student has observed a guitarist onstage, or on the web, playing something very technical, but they “make it look so easy,” and this student mistakenly believes that it must come easily to him or her, in just a few short practice sessions.

Unless these ideas are tempered with a dose of reality, these unrealistic expectations will probably end in frustration on the part of the student and the teacher, or worse, the student choosing to quit learning the guitar.

No one wants that.

Let’s say the student is emotionally immature or has a shorter attention span at this stage, and is only able to reach 25% of the way towards the teacher.

Perhaps he or she needs the teacher to really break down the concepts into manageable chunks, even single phrases or chords. This can be done, if the teacher is willing to reach 75% of the way towards the student.

Here’s something important to remember, especially when things take longer than expected: slow progress is better than no progress.

I’d much rather see a new guitarist take a year to develop solid fundamentals, than to watch them hurry through the process and not grasp the tools mentally or physically.

Music is the long game, and later in our journey, we will still be relying on fundamentals.

If those fundamentals aren’t solid, our playing will be imprecise, and everyone will know it, whether consciously or not.

The worst scenario is if the teacher does not have the capacity to break their subjects down to an accessible process, while the student simultaneously wants results with little or no dedication or practice.

These are the circumstances under which a learning experience of this nature is simply not sustainable.

So, let’s find a more fulfilling scenario, shall we?

The Key to Breaking the Curse of Knowledge

In order to play the “long game” well, I believe we must allow the Lord to cultivate in us two essential virtues: humility and patience.

And it’s no coincidence that these are gifts the Lord offers us in our faith journeys.

Watch for these two words in Paul’s letter to the Colossians, chapter 3, verse 12: “Therefore, as God’s chosen people, holy and dearly loved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience.”

All of these virtues are worth considering, but if we look at humility and patience especially, we can see how their presence or absence can make or break the teaching and learning process.

Humility as a Cure

Let’s say a teacher is not humble, and basically expects the student to learn what’s being taught, even if a different style or pace within the teacher’s wheelhouse could be offered.

The prideful posture of this teacher will inhibit the learning process, leading to the student feeling alone and confused.

But if the teacher is humble, he or she can graciously set a tone of “we’re both learning as we work together,” and there can be great freedom in the learning space.

It may take a few different approaches, but if the teacher is open to how the Lord might use their teaching to serve the student, the teacher can be much more effective.

If a student is not humble, he or she basically self-sabotages their learning momentum, because as a student, they aren’t being teachable. They expect the teacher to make things easy, or they expect results to come with less effort.

Thomas Edison said it best: “There is no substitute for hard work.” And I would say that humility fosters an excellent posture for hard work.

Watch as the humble student sits under the teacher’s leadership and submits to what may initially seem tedious or irrelevant, but turns out to be a progressive, effective approach.

And then the victories come, one by one.

Patience as a Cure

Let’s say a teacher is not patient, and he or she cannot tolerate a student who does not grasp or demonstrate a concept immediately.

How sustainable is that scenario?

Unless the student has nerves of steel and is determined to persevere regardless, I don’t see that lasting more than a few months.

Contrast this to a teacher who is patient, yet still expects a dedicated effort from the student. The teacher sees the student’s potential, and therefore the student rises to that standard.

What if a student is not patient?

Sometimes, the student wants to go faster than the pace the teacher is setting, often with detrimental consequences.

Some guitar skills are like a gourmet recipe – they need to be flavored and seasoned slowly. Rushing those skills (regardless of the fleeting promise of “instant results”), typically causes imprecise playing.

There are always exceptions, but if the teacher senses that the student is eager to move forward before they have a skill locked in, the teacher may need to ask the student to be patient…because future skill development may rely on those early skills.

Another analogy…building a house on a cement foundation that has not solidified could be disastrous for the structure of the house.

But if the student is patient, all sorts of possibilities open up. I once created a song that I knew was beyond my skill set when I composed it. Nevertheless, I was able to capture it on paper. Do you know how long it took me to learn to play that song? Seven years.

Did that require patience? Yes. Was it worth it? Absolutely.

So, with a healthy measure of humility and patience on the part of the teacher and the student, we can be restored to the ideal scenario for learning, with each party reaching out 50% of the way, to bridge the gap.

Conclusion

So, just to re-cap, the Curse of Knowledge is something that no one is immune to.

I haven’t always had the heart of a teacher, nor have I always been as teachable as I am now. But through humility and patience, with the Lord giving me strength, I’ve been able to break the Curse of Knowledge.

This has allowed me to be an accomplished teacher and an eager learner.

If neither the student nor the teacher are humble nor patient, then it’s a recipe for all sorts of dysfunction, and both may walk away from the experience scratching their heads, wondering why it went so badly.

Little did they know they were both under the Curse of Knowledge.

But if both the teacher and the student are humble and patient, watch how amazing the experience can be.

In time, both the teacher and the student will see tremendous results in themselves and each other. No “Curse” to be found here.

Instead, what do we have? Serious fun. Mic drop!

So, as you play your guitar and embark on learning new skills (and there will always be new skills to learn), I invite you to remain humble and patient.

And if you’re looking for an environment where your guitar learning can be enhanced and supported in a steady way with the long game in view, I encourage you to seriously consider GuitarSuccess4U.

I eagerly await the opportunity to serve you there.

And please don’t forget to share this episode with someone else if it has been helpful to you.

I’ll see you next time.